TW: This account contains graphic depictions of physical and psychological abuse.

You have my full permission to share this account.

-K.Q.

I’ve returned to my hometown a few times over the course of my life. Despite my efforts to get as far away as I can from that fucking place, I even went back and tried to settle down there for a few years. There, in that bigoted, shitty little forestry town between 2022 and 2024, I experienced the second-worse domestic violence I’ve ever lived through.

The worst one was twenty-five years ago, only a short drive away, in that happy pink house at the end of the street.

Writing has not come easy these last few weeks. Words seem to spill out of me in a jumbled, furious mess and hit the page as if I hurled them in anger. A year and a half ago I was being abused, manipulated, beaten, and abandoned by a man who forced a cheap $300 engagement ring on me in the hopes that he could abuse me forever. Unfortunately I had become complacent, would no longer fight back, and he became bored with his toy. My money was stolen, my life was ripped away, and my story was twisted to an unrecognizable degree that everyone in my life believed without question. A year ago I started healing, and while I wasn’t so naive to think it would be an easy process, I couldn’t have imagined it would be this hard.

I expected to have horrible days, and I did. I expected to lose sleep. I did. I expected to have a wildly inappropriate period where I drank and smoked and whored around the city.

I mean. I did.

What I didn’t expect — and what upended my life into so much of a blinding rage I can’t even text my stepmom back — was that none of this ended up being the root of all my trauma.

Lately my therapist has been nudging me gently towards talking about my childhood. I waved her off. My childhood was fucked up, I tell her, but it wasn’t traumatizing. She nods. She doesn’t believe me.

So she finds another avenue.

What about when everything ended in hellfire last year? Who did you rely on? Who did you turn to for help?

I laugh, it’s an instinct. An exceptionally hollow laugh I use when something is funny, but not ha-ha funny. Well, I turned to my grandparents because I physically had to, I tell her. He abandoned me in the literal sense — he took our only vehicle and left me stranded on a farm 15km outside of town. I had no way to get anywhere, no way to buy groceries, not that he had left me any money as he locked me out of the shared account that only he could control and insisted we set up. I asked my grandparents to take me to the nearest big city, where the rest of my family was. They did. They had to. I was living in their house and they wanted me out. I asked my dad to host me for a week before my rental became available. He did. He had to. I would have been on the streets otherwise.

No one asked me what my side of the story was. They continue not to ask. A year ago I was met with legal action that threatens to sue me if I publicly talk about the abuse I suffered under that monster. And yet, even in the wake of that, everyone asked him what happened, not me, and they lapped up every psychotic, manipulative, twisted word he said. I was given no opportunity to defend myself or speak my piece. No one tried to get me into counselling, no one stopped by, no one checked in, no one asked me if he lied to everyone. In fact, in a move that has permanently shattered any remaining relationship I had with my grandparents, they even went to the police station themselves and used their connections to make the report disappear.

That must have really hurt you, she says. I laugh. Hollow.

No. Not at all.

I expected my parents to fail me. I expected my grandparents to fail me. I expected my family, who anyone else would openly greet with trust and love, to fail me over and over and over again, and like clockwork, they did. My therapist asks me how I feel about that.

How I feel about what? My family failing me? Why would I care?

She tilts her head at me.

Why wouldn’t you?

Ah. Fuck.

The half-broken lightbulb haphazardly screwed in to The Shed of Repressed Memories flickered to life, and in an instant I became so furious, so deeply enraged, that I sat in bed for hours, shaking so hard I thought I might explode in anger, and typed and deleted about a thousand variations of the same message to my parents and grandparents.

Fuck you. How dare you. How dare you. I hate you. I hate you. I hate you. I HATE YOU.

That was weeks ago. And still, I cannot function. I cannot breathe. I cannot exist without this anger devouring me, and I don’t know where to direct it. I told my therapist that normally I would write about it, and she told me to do it anyway.

Write it and don’t post it if you don’t want to upset anyone, she says. The hollow laugh escapes me before she even finishes.

Or post it, she follows. It’s your story.

I was born in 1994 to two incredibly ill-equipped teenagers. They got married in the same dirty old Civic Centre that’s hosted thousands of teenage weddings, though that was due to the Ultra Conservative Christian undercurrent that flows through that town like cheap wine. Horny teens entering lifelong commitments because their pastor told them it’s a sin to take it in the church basement. My parents had already covered that part — my mother in a flowing maternity gown, my dad questioning his life decisions, the Shotgun Wedding Package ushering in a life neither of them wanted. And lord did I ever grow up knowing that.

My parents got divorced as quickly as they married, the story I’ve been told that he walked in on her fucking another man on their kitchen table. In my limited memories of that time, I lived entirely with my father and only saw her once in a while, though she still lived in town. She walked me to school once, we were an hour late. My dad told me how much of a disaster she was. That was consistent. I always knew how much my mother was failing me.

My dad was still a kid when I was a kid, and we were both welcomed in and raised by my grandparents. To be fair, my early childhood was beautiful. I was the luckiest kid in the world. Where everyone had two parents, I had three. A super cool dad. Two loving grandparents. A big farm to run around on. I have a picture of myself on my fifth birthday, in a frilly white dress, riding around the driveway on my brand new bike. I’m smiling. It’s one of the last photos I have of myself where I’m smiling for real.

The one thing my dad got right is that my mother was a disaster, though I doubt I needed to hear it as much as I did. At some point, she up and moved six hours away and had a different kid. I’d find out much later, 11 years after being abandoned, that she decided that kid was actually worth sticking around for. To be fair, she was as much of a disaster with him as she was with me.

My dad got remarried in that same Civic Centre a few years later for Shotgun Wedding Package #2, my younger twin sisters already born and adorned in lilac-purple flower girl dresses. I was asked to be a junior bridesmaid, though I remember the moment I was asked — my dad standing beside her, encouraging her, and now that I look back with some objectivity, I’m almost sure forcefully making her. I doubt I would have had a place in that wedding without his input.

I’ve often looked back on the photos of that day, because in an effort to torture myself with a lifelong history of being othered, I have the entire album on a flash drive. There are over 700 photos. My sisters are in 102. I am in 9.

But I understand. I, too, would care only for the children I actually birthed. Stepchildren are a black mark on society and should be banished to their bedrooms without supper as often as possible.

In adulthood, I have begrudgingly cultivated a passable, polite relationship with this stepmother. As is the burden of every first child, we spend our lives watching our parents become better and better people, and by extension, better and better parents. I can’t deny that my younger siblings had a pretty decent mother later in life. But in my story, in the dark, hidden, horrible years of 2002—2006, she is a monster. They both are. And because they are well respected, well loved, and have poured far more charisma points into their personalities than I, my story never once mattered. Not to her, not to my father, not to my siblings, not to anyone. Certainly not to my grandparents, or my neighbours, or my teachers, or the police, or anyone who was supposed to protect an innocent child from getting beaten, punched, and locked away. I learned from a very young age that no matter what, when, where, or why, I would always come second to the real family they had built. And just for the simple crime of existing where I wasn’t wanted, I had to take every beating that came and you’d better stop crying and wipe that scowl off your face before anyone sees you, you’re an embarrassment.

Real words, accompanied by a sharp twisting of my wrist that I was told to lie about. It’s a sprain, I told Mr. Gunderson the next day. I hurt it on the swings. He didn’t question it, because I told the fib expertly. My parents were training me every day to be an excellent liar. I needed to be, to protect their image. Nothing took precedence over that. Except for maybe the children they did want.

It didn’t matter what the sin was. I received an equally painful arm twist for asking if Santa was real in the presence of the twins. There were people around, but my stepmom gripped me so tightly and spoke to me with such seething hatred that I knew she’d be beating me within an inch of my life if we were alone. How dare you, she would hiss in my ear. Anything that came close to hurting her babies. Once, at their birthday party, she bought two big sheet cakes that each had a clear plastic lid. She told me to set up, so I put a cake slicer on top of each cake lid. From a ways away, it almost looked like the slicers themselves were dug into the cake. She flipped. Twisted my arm. Why would you do that? Why the fuck would you do that? Huh? When she realized she was wrong, she shoved me away and refused to apologize. When she shoved me, I hit my head on the wall of the rec room. That one off the public pool, the one where every kid hosted at least one birthday. I never had a birthday there. Or anywhere. They even forgot one year. I snuck a candle and a cupcake and sang happy birthday to myself after everyone went to bed. They found sprinkles on the floor the next morning, and she ripped open a bag of my cereal and dumped it on the floor as punishment. Every action I took, no matter how small, no matter how innocent, was an affront. How dare you. How dare you exist. How dare you be here, wrecking my perfect life with my perfect babies. How dare this jackass of a man have this fucking kid without my consent.

As I write this I’m already preparing myself for the ridicule and revisionist history from my family that will follow. The first thing they will say is that I was a difficult child. I was always crying, yelling, upset, and they couldn’t calm me down. Now I haven’t checked, but I guess legally, that would give you the right to beat your kids. After all, how else are you supposed to raise them? With compassion? Understanding? With a five second breather before you fly off the handle and shove a nine year old down the stairs? Hah!

Twice in my life, once in adulthood, and once in childhood, though long past the point of these stories, I had been diagnosed as autistic. I received both of these diagnoses before autism became a buzz word across every neurodivergent person on the planet, but that shouldn’t matter. I am an autistic adult, and I was an autistic child. I still deal with sensory overwhelm in the extreme, and often need to remove myself from situations and go through a myriad of soothing techniques before I can return with any sense of calm. As a child, I didn’t have these skills yet. No one was patient enough to hold me through the overwhelm and teach me. They bit back with fire. I learned to suppress my emotions because that was the only way they tolerated my presence, and when my feelings inevitably burst forward, I paid the price.

The only bit of grace I am willing to extend to the adults in my life is that autism was horribly misunderstood at the time, especially in girls. But it doesn’t take away from the fact that my parents, in full view of the entire neighbourhood, who could not have ignored the screams and pleas for help echoing down the cul-de-sac, mercilessly and repeatedly beat an autistic child for the unforgivable crime of being alive.

Every one of these memories is jumbled and out of order. Despite knowing they exist vaguely between the 1st and 6th grade, I could not tell you when each happened. They exist all at once, and also not at all, in some far-off corner of my mind that silently and insidiously informs every piece of my existence.

The thing you have to understand about that time period, if you weren’t raised in it, is that society was still deep in the spanking-your-kids era. People politely looked away if you needed to discipline a child in public. It wasn’t until much later that people started to question whether or not striking a child was appropriate or even ethical. Now, people are horrified. If you want to spank your kids, you do so in the privacy of your own home. You don’t let anyone see. And you certainly don’t admit to it.

But I wasn’t spanked in public. They were very careful about that. They, and particularly she, would find other ways to torture me physically. If I didn’t look happy enough I got a sharp pinch on the back of my neck. I had my arm gripped and twisted. I was pushed and shoved when I wasn’t moving fast enough. I was smacked upside the head when no one was watching. But they never, ever spanked me in public. And in knowing that, and looking back on how widely accepted it was at the time, I realized something.

I wasn’t being spanked. I was being beaten. I was a child, a confused, frightened child, who was regularly being beat up, in every literal definition of the word, by my parents.

My spankings left me with deep, aching purple and blue bruises that would hang on for weeks and ended up causing permanent nerve damage. That’s not a joke. I have literal, lasting, permanent, irreversible nerve damage from how hard they hit me. In report cards, they wrote home that I was having trouble sitting still in class. I couldn’t sit still. Every day I was adjusting. It hurt to sit. My parents knew that, they knew why. They blamed it on me being a difficult child. My teachers smiled and agreed.

I first realized that I had actually been beaten when I was 21, sitting in an early psychology class in university. We were separated into groups and instructed to talk about our thoughts on corporal punishment. It was there that I realized everyone else in my group had also been spanked, but their experiences were vastly different from mine. One strike. Maybe two. Never enough to leave a bruise.

Certainly not the experience I’d had spent over my father’s lap, his elbow digging into my back and compressing my lungs to the point where I was gasping for breath. They didn’t share my story of being hit dozens of times, full force, with every bit of strength an adult man could muster. Their parents didn’t seem to spew hateful comments towards them while they were punished. But mine did.

WHY smack ARE smack YOU smack LIKE smack THIS?! smack WHY smack DO smack YOU smack MAKE smack ME smack DO smack THIS smack TO smack YOU?!

And then he would beat me without words, taking out every bit of anger he’d collected from the other corners of his life. I played the part of his faithful punching bag, and I played it well. My stepmother would hang out with the twins upstairs and watch TV while my screams drowned out The Backyardigans. They all pretended not to hear.

My father could not control his rage. He hated everything. He hated his life, he hated his wife, he hated his kids. Perhaps the most sickening thing about that house was that to the world around us, our home was filled with art. Drawings of sailboats and happy children and fields of flowers adorned the walls, and their friends would come in and ooh and aah at all the pretty pictures. Beneath each, a place my father had punched a hole in the wall.

He was an excellent liar, too. Of course I learned it from somewhere. In the time he was beating me senseless he opened up a business, he sat on City Council, he even ran for mayor. Everyone loved my dad. He put on a smile and drew a beautiful white picket fence around his family. And there we sat, For Display Purposes Only, and every year in the family photos my smile got smaller, and smaller, and less genuine, and one day it disappeared, and then the next year, so did I.

I was sent off to live with my grandparents when I became Way Too Much. In a parallel dripping with so much irony even a YA author wouldn’t write it, I watched myself repeat the cycle in my own life. A man, who was an almost psychotic-level expert at appearing kind, who claimed to love me, would come home and abuse me before lying to the world and eventually abandoning me when he was sick of my existence wanted to move onto the next shiny thing.

My father, my fiance, my story doomed to write itself over and over and over and over again.

The worst thing I could ever do to them was dare to flinch in public. Oh, it made them look terrible and that was indeed the gravest sin. That little girl flinched when her dad got a little too close. He must smack her around, the town would whisper. My parents would weave a web of lies to protect their image, and the people would buy it, and back at home I would pay for my misdeeds.

One of the core memories from my childhood is watching her rip up a book of mine. I don’t know why that one affected me so strongly, but it did. It started because I flinched and panicked, and she hated that more than anything. You must not flinch. Ever. You have to understand — I was terrified of my parents. They hit me whenever they wanted, all the time, without prejudice. I never had a moment’s peace unless they were gone. So that day, when she was in a bad mood and stomped into my room because she needed to take it out on someone, I flinched. I flinched hard. And that set her off like I’d punched her right in the face. She lunged towards me, discarding the cordless phone she was holding in her hand on my bed, and I panicked. She was reaching for me to beat me senseless. So I fought back. I picked up the phone and threw it in her direction, though I’ve always had a terrible arm, so it hit the wall. And god that set her off too. She screamed about how I had no respect for her fucking things, how if I wanted to wreck her stuff, she’d wreck mine right back. She swept entire shelves of my belongings off my bookcase, ripped clothes off of their hangers, and grabbed the book that was on my pillow. It was a beautiful blue paperback copy of Aquamarine, a mermaid silhouetted in the cover, and she reached in and ripped out pages 28-76. Screaming, the whole time. Never stopping screaming. She hated me. Hated me. And nothing she could do to me could make me understand how much she hated me, and that made her hate me more. She threw what remained of that book at me, leaving a scrape and a bruise right below my eye. I was instructed to lie to my teachers, and as punishment I was not invited to supper that week. My dad would bring a plate of food and leave it outside my door at 9 pm. I was banished to my room in the basement while the real family lived their happy lives upstairs. God forbid I ever talk to them. I was not wanted.

Most of the time I would hide in my room and read, because if I was reading, I wasn’t bothering them, and if I wasn’t bothering them, they usually wouldn’t hurt me. I read a series of books called Losing Christina, in which the main character is silently abused and psychologically tortured by people who hold the respect of the whole town. I reread those books more than I read anything else in my life. I was Christina.

This isn’t to say they didn’t show me off when it benefitted them. I was an excellent musician. I was the best. There was no contest. I won everything, every time, and I was good. Every March or April, when our local Music Festival came around, they would dress me up and cart me around to the different churches, and when I won all the classes and certificates and scholarships and prizes they would make sure to show me off to the world, beaming with a pride so fucking fake and performative I can’t even write about it without my blood boiling.

There was one year in that house that overlapped with my sisters also being in music festival, and I got the beating of my life for daring to talk about all the prizes I won in front of them, who didn’t win any. Right. I should have known. The wanted children. They come first.

I put a lot more responsibility for my childhood on her, and let my dad off relatively easy. I haven’t figured out why, but if I was to guess, I’d say it’s because even an abused child still wants to be loved by their parent. And she was never a parent of mine, she made that clear. She would erase me from her existence if she could. So all I was left with was him, and despite the fact that he failed me, he beat me, he hated me, I couldn’t hate him back. I just wanted to be loved.

That’s extended into adulthood. On the surface, I have a fine relationship with my father. Maybe even good. But let me be clear: this comes at the expense of me ignoring, rewriting, and repressing the abuse I suffered under his hand.

The Happy Pink House At The End Of The Street is still there, still pink. Years of weather have washed it into an ugly peach colour, but it still stands. Along my street were other families with kids my age, and I often wonder if any of those kids heard my screams and knew what I was going through. Did they know all that time? Did Shayne, or Samantha? Did Amy or Shae, or Craig or Reese? What about Shelby, or Bill, or Carrie? Any of them ever hear me screaming for help, pleading for my life, at the end of the cul-de-sac? Did their parents?

We were driving home. My dad in the driver’s seat, my stepmother in the passenger’s, the twins in their booster seats strapped into the middle row bucket chairs. And me, in the back. We’re driving along 3rd St, less than a minute from the house.

I don’t remember why I was upset, only that there were several years in a row where I wasn’t anything else. I was crying, I was overwhelmed, I couldn’t stop. I wanted to die. Even as a young child, I wanted to die so badly. The twins were crying because they were little and the environment was loud and chaotic, and something in my dad snapped. Even more than it usually did. He pulled over, slamming on the brakes so hard it knocked the wind out of us. He got out, slammed his door, and came right back with a speed and a force I couldn’t even register before he punched me square in the chest with his full strength. I couldn’t breathe. I struggled for breath for hours after. In an x-ray, it’s been revealed that he broke a bone that healed wrong. Still, to this day, that moment is one of the most painful things I’ve ever experienced.

Some amount of time after that, I decided to break the cardinal rule and tell an adult what was going on. I had to take that risk, even if it made them so furious they might try to kill me. So after a weekend sleepover with my grandparents, when he came to pick me up, I planned out my timing and told them everything. I remember standing by the front door, him rushing us out, me refusing, running into my grandmother’s arms, and the words spilled out of me. I was terrified. I needed saving. He beats me, he hits me, he hit me in the car, he hit me in the chest, he’s gonna hurt me again, don’t make me go back, please, please—

“Oh god, Kelsey. Don’t tell lies like that.”

My grandmother, in a second, doomed me to one of the worst nights of my life. I have almost no memory of what followed, but I’d pushed it too far. I wasn’t supposed to tell. I remember him picking up a chair and shattered my ceiling light, covering us both in glass. From what I remember my stepmom took him to the hospital. I was left to fend for myself, bleeding from my head, my arms, my foot. I cried and thought of how much I would have to work to hide this one from my teachers.

I replay these moments in my head. I have to. I have been told so many false versions of my own history that I can’t trust anything but my own memory. And what I do know is that he beat me to the point that he should have lost his kids. He didn’t apologize. He didn’t acknowledge that he did it. And when I told an adult, he lied to their face.

So I ran away.

But very few children are successful at actually running away, and though I tried a few times over the years, I was found every time. And every time, he was furious. Furious. I’ll always remember why he was angry at me. Not that I had ran, not that he might have lost me, but that it made him look so bad.

Once he loaded me up in his car and drove me out to the middle of nowhere. I’ll never forget what he said to me on that car ride. If you don’t want to be a part of this family, you can fend for yourself. See how happy you are without my roof over your head or my food in your stomach. I was hysterical. What child wouldn’t be? Finally he stopped the car, and in between the sobs of a terrified 9 year old on the brink of being abandoned in the wilderness, he punched the steering wheel and yelled at the top of his lungs that he couldn’t actually leave me there because he’d get in trouble. People would think badly of him. I was making him do this. It was my fault. He drove me back into town and I faced my life of beatings again.

I finally escaped when their marriage imploded. It was on the brink of ending, every single day was a screaming match, and they both blamed me. I was the most hated person in my family. I was hated more than I’d ever seen anyone hate another person before. They looked at me with no warmth, no love, no hope, just hatred and disdain and a cold, bitter rage I don’t have the ability to put into words. I was a lost cause. I was a problem child. No matter how much they beat me, I was not getting easier to deal with, and it was ruining their marriage. They let me know it.

And so, I got sent away.

Life with my grandparents was easier and calmer, but by this point I had been so traumatized that I had no idea how to act or react to anything. The adults in my life continued to ridicule me, citing me as having behavioural issues. I recall that no one ever wanted to know why, they just wanted me gone. I was committed to psychiatric care twice as a teenager, once after a failed suicide attempt at 14, and once because my father enrolled me in an equally abusive boarding school and I tried to run away. When he caught me, he yelled that he didn’t know what the hell to do with me anymore and kept me there on psych lockdown for the next three weeks. It was his preferred way of dealing with my existence. Hit her until she behaves, or lock her up and get her out of his sight.

I wasn’t worthy of any other methods.

My siblings, though — they were worth the world. They got beautiful parents. Loving, kind, imperfect people who knew that they had to fix themselves in order to give their children a better life. I am so happy for my siblings. I harbour no resentment towards them. I am so exceedingly joyful that they get to experience a life without the trauma I carry.

But I can no longer be silent about the abuse I suffered. I have carried this, alone, at a great personal cost, for far too long. I have held this silently inside myself because I felt responsible for protecting a family that has become much better people than they were. It has always been a silent understanding between me, my father, and my stepmother, that I would never dare speak a word about what happened to me under that roof. It would hurt them. It would hurt her appearance as a loving mother of three. It would hurt his appearance of a kindhearted activist. I understand. I have given you the gift of anonymity, of being able to walk away with no repercussions, of still getting to achieve everything you ever wanted in life despite your twisted, little demon child that you beat without remorse and then threw out to the wolves.

No longer.

This is my story. I am taking it back. For the first time in my life, no one gets to have an opinion on whether this story gets told. In telling this, I break the ongoing abuse I suffer at the cost of holding their histories in silence.

I am getting better. I am healing. Without them. Without anyone. I am the most goddamned resilient person I have ever met. I am so impossibly strong. I can carry lifetimes of trauma that most people would buckle under, and I do it with a thousand times the grace that one could ever hope to have in my situation.

I know that my account will be called a lie. That is a given. Just me being a woman recounting my abuse opens me up to ridicule and accusations. I know it will be challenged. I know their friends and their colleagues and the family and the new spouses they have lied to will read this, who know them as People and not as Parents, and they will say to themselves that they can’t possibly be capable of such atrocities.

But the reason I am posting this and making it public is because this account is 100% true, and that truth is known to the three people who matter most: me, and them.

I cannot finish healing from this until I admit how much of my life has been twisted and tortured by the abuse I suffered at the hands of the people who were supposed to protect me. I cannot move on, or be happy, or trust anyone, until this story is told, and I have said my piece.

This story is told. I have said my piece. I will suffer punishment for this, as I always did, I will be cast out and blamed, as I always have been, and none of that will come as a surprise. But from this point, I can finally start to move on. I can accept that I was not loved. I was not protected. I was abused. I know it, and they know it.

I need no other validation.

Fin.

A collection of evidence backing my experiences, despite my family’s attempts to lie and bury this:

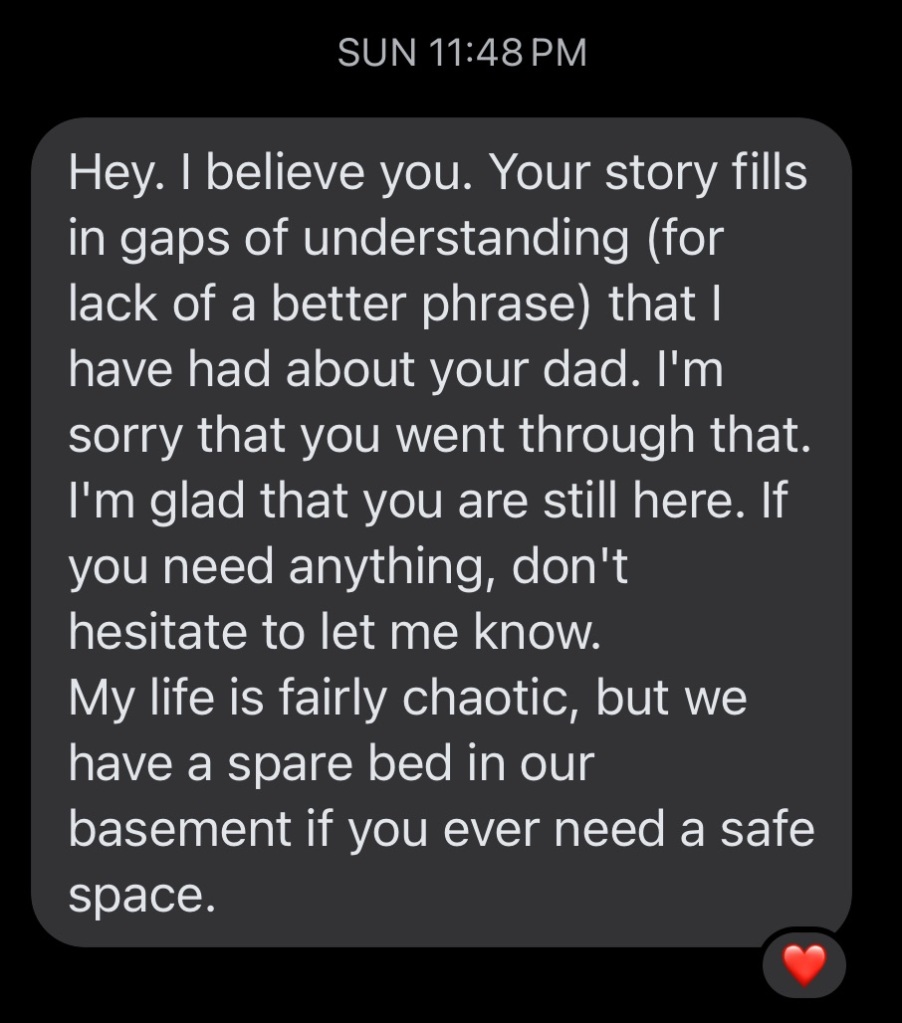

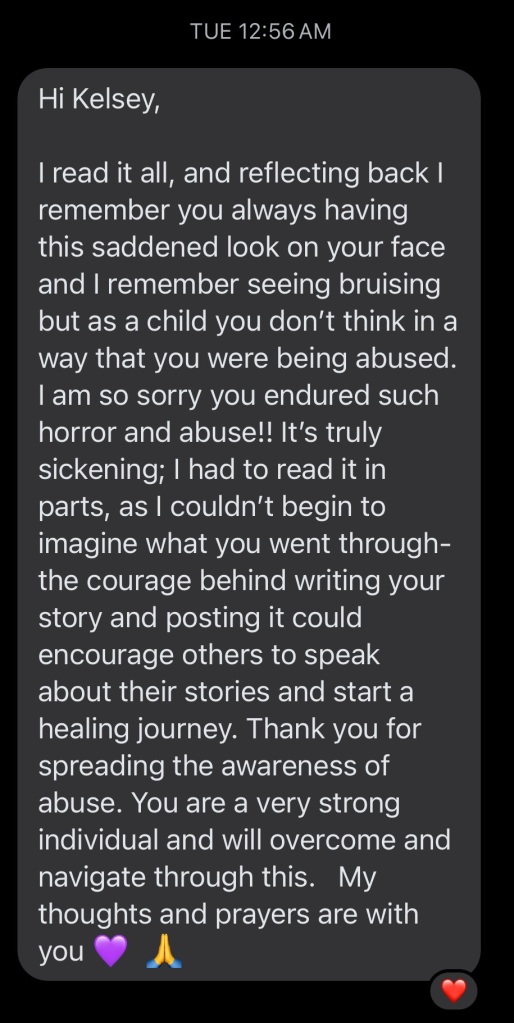

Leave a comment