In a wooden cabin perched over the waters of a Quebec lake this summer, my friend and I lounged on an old couch while she tuned her guitar. We were there for the weekend, friendship newly minted, having only met each other the night before.

In a desperate attempt to have a social life in a new city, I’d caved and joined a friend-making group. And the friend-making group, in all of its feminine wisdom, sent us to summer camp.

Adult summer camp.

I’m setting this up as if I didn’t have a wonderful time. It was great. I spent most of my time on a floating dock with this view:

And in the evenings, 30-or-so 30-somethings all gathered like a gaggle of schoolchildren around the campfire. We got led in song, reflection, and unlike my days at Bible Camp, I was allowed to get absolutely toasted in the parking lot.

Bible Camp would have been a lot more fun with weed.

After we’d all been tired out by camp games like “Pop This Balloon Without Using Your Hands” and “Get All Your Team Members Through This Hula Hoop”, my new friend and I took advantage of the afternoon lull and settled into the quiet of our cabin.

In the weeks leading up to camp, the organizers sent out a survey asking what kind of cabin we wanted to be in. Did I want a completely silent cabin with no disturbances? Well that doesn’t sound fun. Nope. Do I want to be in the party cabin? Music all the time? People coming in off the beach to hang in our common area? Ugh, even worse. I selected something in the middle, and so did four other people, and our fun-but-not-that-much-fun-cabin was born.

The cabins were all aligned neatly in a single row down by the water, save for two: one that sat in solitary near the boat launch, and one hidden at the top of an impossibly steep hill.

I climbed that impossibly steep hill twenty seven times. I counted.

But to be fair, that impossibly steep hill was worth it. Both in the view I got every morning with my coffee:

… and in the quiet solitude that led to lazy afternoons, curled up on the couch, listening to the strumming of a guitar.

A few chords in a row caught my ear, and I half-recognized the song she was playing. I tried to make out what I was listening to:

No, your mom don’t get it / And your dad don’t get it / Uncle John don’t get it

And you can’t tell grandma / ‘Cause her heart can’t take it / And she might not make it

After a few more lines I finally caught why I knew it:

There’s something wrong in the village… with the village…

Give the song a listen. It’s a beautiful one.

To be clear about the lyrics: ‘The Village” by Wrabel is a trans anthem. It was not written for me. The song explores the grief that comes from trying to live authentically when the whole “village” turns on you. And as a queer kid who… well, went to Bible Camp, some of the lyrics hit me hard:

Feel the rumours follow you / From Monday all the way to Friday dinner / You got one day of shelter / Then it’s Sunday hell to pay, you long lost sinner

Well, I’ve been there, sitting in that same chair / whispering that same prayer half a million times / It’s a lie, though buried in disciples / One page of the Bible isn’t worth a life

Because my friend has the voice of an angel, that song remained stuck in my head far longer than I welcomed it. And because my brain is only capable of clinging onto two 8-counts at a time, the chorus repeated in my mind for weeks on end:

There’s nothing wrong with you / It’s true, it’s true / There’s something wrong in the village / With the village

The only other time I’d heard any reference to “The Village” was in conversations about raising kids. “It takes a village to raise a child” was more or less the mantra of our parents’ generation. Well, I had young parents. Maybe my grandparents’ generation. In any case, there was a point in history where The Village existed.

Now, the only time I hear of a village is in the negative. “We don’t have a village anymore.” “Where is the village I was raised with?” I’m almost waiting for some boomer-led news outlet to hit us with a “Millennials Are Killing The Village Industry” headline.

While debated amongst experts, the phrase is generally attributed to an African proverb. It tells us that in order for a child to develop and thrive, it takes the work of the entire village to get them there. The onus is on collective society at large to create a safe, healthy environment where every child can flourish.

I stumbled across an academic article that attempts to define the concept of The Village. As Reupert and colleagues write, The Village “requires an environment where children’s voices are taken seriously and where multiple people (the “villagers”) including parents, siblings, extended family members, neighbors, teachers, professionals, community members and policy makers, care for a child.” (Frontiers in Public Health, 2022).

Reading that stopped me in my tracks. Community members? Policy makers? Caring for children?

I must have missed the cold front that came through when hell froze over.

Whichever vengeful God placed me on this Earth at least had the decency to place me in Canada, so our policy-makers aren’t quite as misogynistic and …death-y as other countries right now. However, we’re not exempt from the broader attitude rippling across society at large: you’re on your own, kid.

When I was a young child, my parents relied on what little of The Village we had left. Both of them worked until 6 pm, and after-school day care, for three kids, five days a week, wasn’t something we could afford. From the tender age of 6 I walked home from school, grabbed the key under the mat, and let myself in. Not much of a village.

And yet, it was.

The village was my teacher who made me wait in the classroom until everyone was out and then walked me across the street.

The village was stay-at-home moms who watched me from their kitchen windows until I locked the gate shut behind me.

The village was my grumpy next door neighbour who bolted over with a fire extinguisher when I set off the smoke alarm.

And the village, back then, was even an elected official signing free classroom lunches into law.

But today The Village is non-existent. Where people used to ask for help and provide it willingly, we now seem content to isolate ourselves and shatter what little community we have left. The concept of a village is fragmented, and for the average child in today’s landscape, is something they will probably never experience.

Family breakdown, economic pressures, and a “do-it-yourself” mentality have stripped us of the one thing that makes us so human: connection.

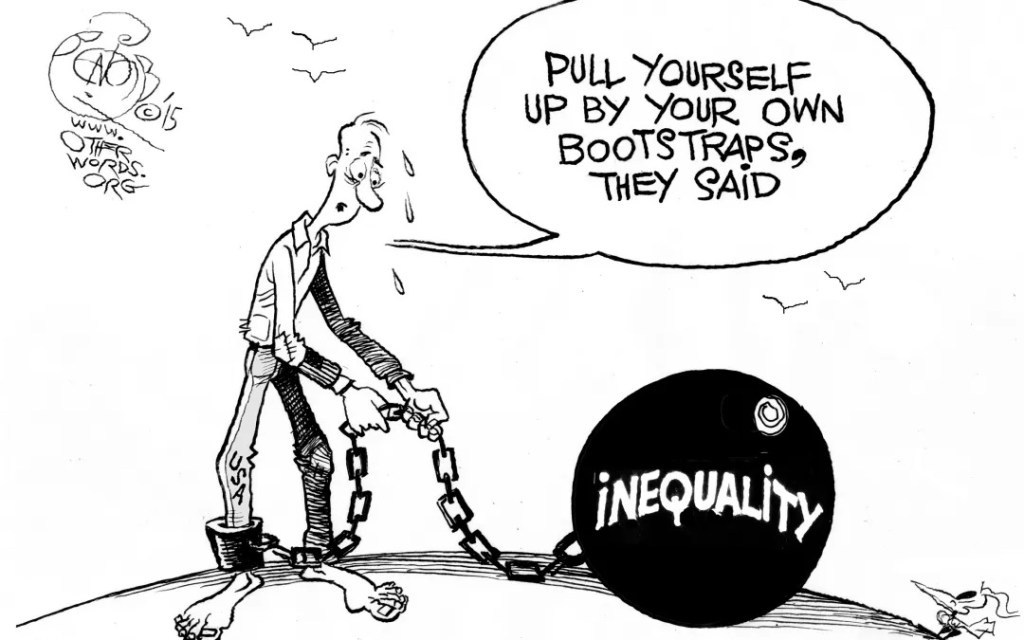

My generation struggles with a question that few have had to struggle with to this extent: Is it even ethical to bring kids into this world? Of course, previous generations have lived through fascism and war and civil unrest and giant sweeping shifts in the way society functions. Who are we to consider ourselves so special, so hard done by? As my grandfather is fond of saying — pull yourself up by your bootstraps.

In a recent post I asked myself the question: are we truly living in unprecedented times? I settled on this:

We can only make an educated guess as to whether or not we’re in the worst of history. In fact, ‘unprecedented’ doesn’t even skew toward to the negative in definition: it simply means never known or done before.

By that definition, the loss of The Village really is unprecedented. Somehow, in our global effort to connect everyone on Earth, we lost what it meant to be connected in the first place. While I can’t count myself out of the online masses, given that I owe my platform and career to TikTok of all things, I admit that people aren’t the same as they were before they got their hands on the internet.

We no longer engage in conversation when we don’t know something. Why would we, when we have all of the world’s information ever recorded on our phone? No more memories of the 1998 Christmas blowout where Mom and Uncle Owen argued over who the actor in Footloose was for hours on end because no one had the answer in their pocket. The answer was in a book, or in a movie review in a newspaper, or on the cover of the VHS tape, or incorrectly nestled into Uncle Owen’s mind as definitely Patrick Swayze. No more memories of the entire family adjourning to the living room to watch Footloose on Christmas Day and your mom screaming “KEVIN BACON!” when he appeared on-screen. No more memories of the fit of laughter that led to you spraying Diet Pepsi out of your nose and all over Grandma’s brand new Christmas sweater. No memory of Grandma consoling you that it was alright.

Are we still making these memories? I don’t think we are. We’re missing out on formative moments because we’re all too busy trying to capture and polish a version of our lives to put on display. Why would we invest in the relationships in our immediate vicinity when we can gain the approval of The Entire World?

In my opinion, there’s a reason people reach a breaking point when they live on the internet: we weren’t designed to be this connected, not in this way. Not in the way where we can’t escape the constant stream of collective consciousness. Not in the way that we’re expected to only be a text or phone call away at all times. Certainly not in the way that we are experiencing the lived trauma of everyone, everywhere, all at once, through a screen.

In our quest to find connection, we accidentally stumbled upon connection’s kryptonite: overwhelm.

Our circles are supposed to protect us from the overwhelm. Are you cold? Here is shelter. Are you hungry? Here is food. Are you scared? The mothers of the village will hold you.

But we abandoned the village. We traded relationships for platforms. Authenticity for clicks. Love for likes.

Humans crave The Village. It’s innate — we can’t get away from our desire for connection, even in a society that thwarts our every attempt. It’s why friend-making groups even exist. It’s why on a Tuesday night, in between over-poured sad girl glasses of wine, I spent hundreds of dollars to go on a camping trip with girls I’d never met. It’s why my friend, in the midst of a relationship crisis, sought out the company of other women. It’s why despite all of our best efforts to be Very Very Social, nothing we ever do online feels like socializing.

Because people need people. People need The Village.

My friend and I — along with our other friend, who we adopted as ours at that same summer camp — attended a concert together a while ago. I have exactly one photo:

Yes, it was Green Day. We are, above all else, children of the 90s.

I only have one photo because I genuinely forgot to take my phone out the rest of the night. I was having so much fun. Do you know how long it had been since I had fun? The concert — with my phone forgotten in the pocket of my straight-outta-the-90s black denim overalls — was the first time in years I just surrendered to experiencing the moment. I was a little high. I was very drunk. It was a concert. I was with my friends.

I had started building my village again.

The problem with us saying that there’s something wrong with the village is that we place the power to fix it in other people’s hands. Yes, I want the village back, but I’m also the village.

So I started introducing myself to people on the street. I ask for a cup of sugar sometimes. I gift my neighbours little things I make. I ask my friends out for coffee. I’m trying my level best to build relationships out of thin air. And as an extremely cynical person, none of this is easy. It’s a slow and painful and awkward process, and you’re going to hate to hear this, but it’s working. My neighbour followed my lead and made a mom friend in the neighbourhood. They swap play dates with the kids so the other one can rest.

We are rebuilding the village.

Sources

Reupert, Andrea, et al. “It Takes a Village to Raise a Child: Understanding and Expanding the Concept of the “Village”.” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 10, 2022, article 756066, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.756066.

Leave a comment